in search of modernity

Cartier and Islamic Art

Jewellery exchange between the Islamic world and the Christian world has existed for millennia. Byzantine jewellery is at times indistinguishable from early Islamic jewellery, and cross-cultural influences still exist in the traditional jewellery worn around the Mediterranean. These are all evidence of a long, shared history. But what happens when a high-end European jeweller feels ‘stuck’ in his repertoire, and actively seeks inspiration in another culture? The book Cartier and Islamic Art is a lavish publication exploring how eastern designs formed a source of inspiration for the work of one of the most famous jewellery houses of the West.

This book accompanies the exhibition of the same name, that was held in Paris and will be on view in in the Dallas Museum of Art from May 14, 2022 to September 18, 2022. A point to note in advance is that this is a book about aesthetics and forms, not about cultural meaning or significance: it is an art historian exploration of the creations of Cartier. The terminology used reflects a Western point of view entirely, such as the definition of what ‘Islamic arts’ actually are. You will find not just pieces created by Islamic cultures, but also jewellery from the Hindu world, and the ‘arts’ themselves exclude for example calligraphy. Let me elaborate on that a little. As for example Charlotte Huygens explains in her essay ‘On the History of Art in the Islamic World’ in the 2018 publication Splendour & Bliss, the term Islamic Art was coined in the colonial era, when the Islamic world was viewed as a monolithic entity, the counterpart of the West – the era in which Cartier started out to look for inspiration. That world view shines through, amongst other things, in the imprecise way the Cartier archives label both their creations and its inspiration: ‘Persian’, ‘Arab’, ‘Oriental’ are regularly used interchangeably. Nowadays, the denominator ‘Islamic Art’ is still used, but with the connotation of its cultural pluriformity, and it is to be understood as such in this book as well. The many essays in this book however do much more than simply illustrate how Cartier jewellery was inspired by Islamic art. They show us how to what extent abstract Western arts, notably Art Déco, are indebted to the Islamic world, and that is a great deal.

The essay on ‘Islamic Art “revealed”: a path toward modern design’ is one of the most powerful contributions in this publication. I am usually wary of wording like ‘revealing’ in the context of the Islamic world, but the use of quotation marks here reflects the sentiment of the essay itself. Its authors unpick how the Islamic arts were introduced to a European audience: through wars, displacement and colonial greed (p. 40). The success of world exhibitions and the subsequent adaptations of Islamic art forms lead to new experiments in the design field, moving away from Orientalist interpretations (p. 46) to the first attempts at abstract expression. This historical context is pivotal for understanding the jewellery created. The private collection of Louis Cartier is central in the next essay, where stunning manuscripts and inlaid works were not just collected to satisfy a personal curiosity, but also to be shared and loaned to exhibitions that in turn furthered European interest in the Islamic arts.

The arts from the Islamic world and beyond did not just form design inspiration, but brought new techniques to Europe as well. The essays on India explore how wealthy clientele from India brought their jewellery and gemstones to Cartier in order to have them updated or set in new jewels. These latter however had to conform to Indian tastes, and so the technique of stone setting known as kundan found its way to the Cartier ateliers, along with other ways of looking at forms and types of jewellery. The essay on Cartier’s Lexicon of Forms, although it uses terms like ‘Arab’ and ‘Persian’ loosely, showcases how forms derived from Islamic art and architecture were translated into design elements: not as mere copies though, but adapted and transformed into a new visual language. Even the graphic arts of Cartier were transformed based on the structures and patterns learned: the influence of Islamic art is profound and stretches well beyond jewellery design.

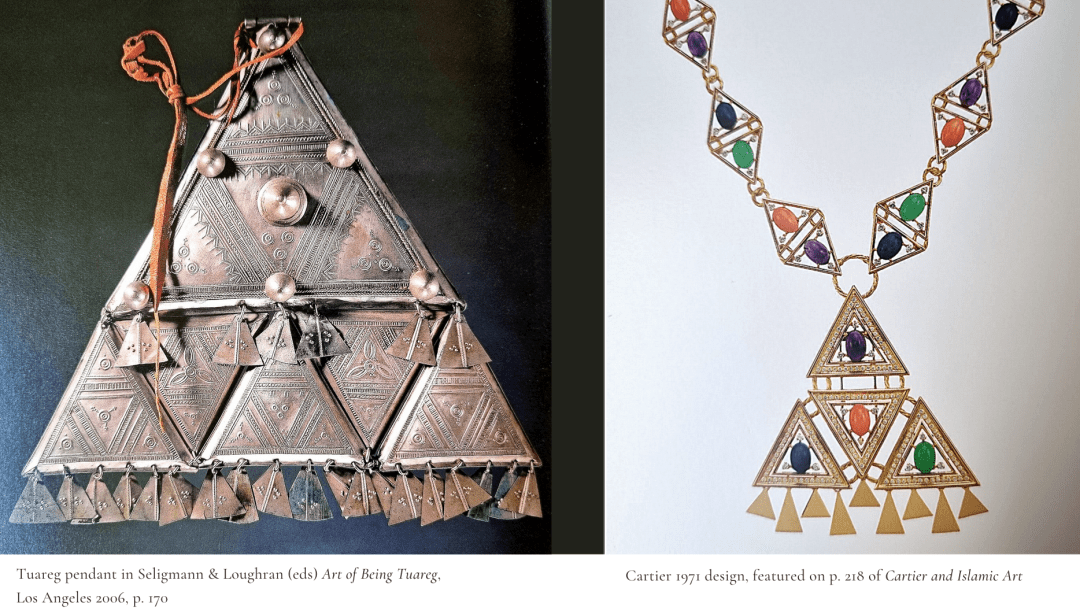

As the timeframe in which the ‘Lexicon of Forms’ came into existence, with all its imprecise denominators as I pointed out above, was at the apex of colonialism, it will not come as a surprise that the origin of some designs is not always clearly identified. An example is the necklace featured on p. 218, designed in 1971. It is described as inspired by Berber (which we now would indicate as Amazigh, following the people’s wish to be named in their own language) fibulae from Kabylia in Algeria (p. 187). While that may certainly hold true for the necklace itself, the pendant seems to me to be based in Tuareg tereout tan idmarden pendants as worn in the Hoggar mountains of Algeria. I was pleasantly surprised to see jewellery of ordinary people (instead of the possessions of shahs and Mughal elite) serve as inspiration for these high-end creations as well, and wonder if other contemporary jewellery examples that form part of North Africa’s and Southwest Asia’s heritage might still go unidentified.

The design and photography of this book are simply fabulous. Both original pieces and Cartier creations are photographed in crisp clarity. The large format allows for endless comparing and admiring, and what I particularly loved are the blow-ups of tiny details at the beginning of each chapter and even the cover: the cover image is a detail of a cigarette case, only 8,7 cm in height! Short intermezzo’s, like a brief essay on the pen boxes of the shah, Mughal jewellery from India or book bindings, provide informative examples on how details traveled to other designs. Each chapter is well referenced: don’t skip the endnotes, they feature many more details and discussions!

Cartier and Islamic Art is a detailed journey into the creative process of this famed jewellery house, placed in the context of its time. From inspirational exhibitions, visits and experiences, via drawings and designs to the breathtaking jewellery creations, this book places western designs and its teachers from the Islamic world side by side. For me, this book was an eye-opener in how deeply rooted abstract jewellery of the early 20th century is in Islamic art: a development in the field of jewellery that has been explored in depth for the first time in this publication. It is a visual feast of stunning, elegant Cartier designs and a wealth of superb original artworks from Southwest Asia, North Africa and India, accompanied by in-depth essays: I am sure you will thoroughly enjoy both!

Cartier and Islamic Art. In Search of Modernity. by Heather Ecker et. al. (eds). Thames & Hudson, 2021

315 pages, full-colour, in English. Available with the publisher, in bookstores and online.

The book was received as review copy by the publisher.

More book reviews on jewellery & art? Browse dozens of books here!

Or join the Jewellery List and receive new book discussions automatically in your inbox!

Sigrid van Roode

Sigrid van Roode is an archeologist, ethnographer and jewellery historian. She considers jewellery heritage and a historic source. She has authored several books on jewellery from North Africa and Southwest Asia, and on archaeological jewellery. Sigrid has lectured for the Society of Jewellery Historians, the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden and the Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center, among many others. She curates exhibitions and teaches online courses on jewellery from North Africa & Southwest Asia.