How to clean ethnic silver

three methods

How to clean ethnic silver

Updated Jan 10, 2024

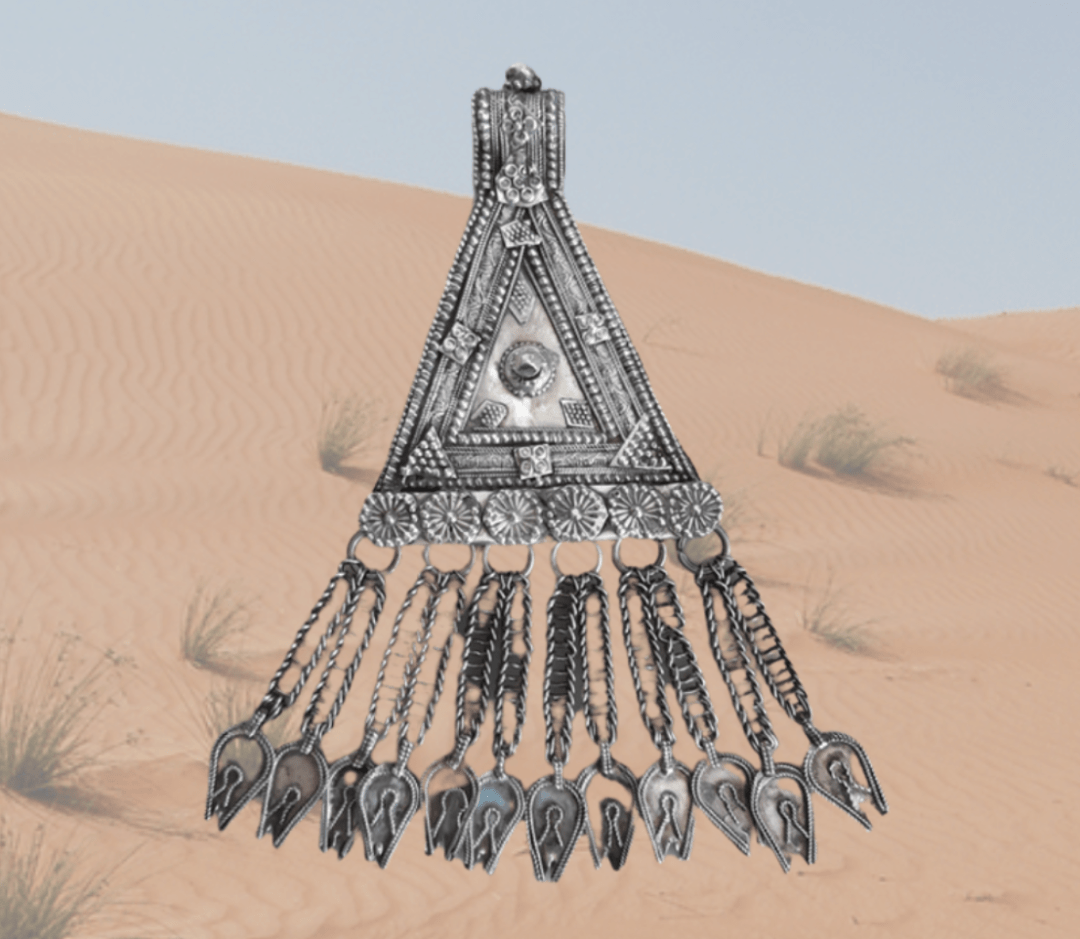

How to clean ethnic silver jewellery? And should silver even be cleaned in the first place? This article gives 3 practical methods – and what mistakes to avoid!

Should I clean ethnic silver jewellery?

Jumping right in here: that dull layer with which you found it in that antique store or in that dusty market stall…? That is not ‘authentic’ or ‘original’: the previous wearer would have taken pride in her jewellery glinting in the sunlight. Wearing it on a daily basis would itself have contributed to that shine. So yes, I do recommend to clean your jewellery.

Also, that dark coating you may have found it with, is not ‘patina’: this is just plain dirt. Seeing people claim that you should not clean darkened, dusty silver because of its ‘patina’ just makes me want to scream, in all honesty. Such lack of insight is actually endangering the quality of your jewellery.

Over-cleaning, however, should be avoided. Once the major layers of dirt and grime have been removed, a little tarnish actually protects your silver. Every time you clean it, you remove just the tiniest bit of the surface, leaving your silver exposed to another ‘tarnish-attack’.

You will want to keep an eye on how it develops, but don’t clean it too often.

And finally: proper cleaning of a heritage item is a professional’s job. You don’t attempt to restore a painting by yourself, either, right? The above considerations by the way all stem from my experience in the museum world. That includes the fabulous work restorers do, and how wrong choices regarding object maintenance gives them nightmares.

In any case: when you do need to clean silver, here are 3 methods that you can use at home, along with their advantages and disadvantages.

Before you start cleaning your ethnic jewellery…

…read this, if you haven’t already. There are a few things to consider before cleaning, that have to do with the silver content of your jewellery, loss of information and proper documentation.

The tips I’m sharing with you below are relevant to jewellery entirely made of good silver. If your jewellery contains any other materials such as wood, enamel, coral, beads, or is of an unknown alloy, bring it to a professional instead.

Another check to do before you start cleaning is the construction of the piece. Hollow pieces, such as amulet containers or anklets, should not be in contact with water: when water gets in, it is very difficult to get out and it may damage your piece from the inside out. For these, I recommend seeking help of a professional cleaner, too.

Because as I said earlier, cleaning and restoring jewellery is an actual profession. It requires years of study and a serious understanding of chemistry, metallurgy, gemmology and much more.

Anything more complex than a solid silver piece benefits from the care of a professional, so if you do own complex or composite pieces, or are having doubts whether your should attempt to clean anything yourself: do yourself a favour and treat your jewellery to a spa day with someone who knows what they’re doing. Ok?

Method 1: cleaning cloth

Silver can show discoloration after a while. It gets a little duller, and may show a yellowish or dark hue. This is easily remedied by buffing it with a silver cleaning cloth: all you do is rub firmly. Usually when your fingers start to hurt, this is a good sign you’re well on your way and you will see the silver surface return to its soft shimmer. This is sufficient for most jewellery as part of your regular upkeep.

Pro: easy to do

Con: basically nothing, although those fingers hurting is real

Method 2: polishing

When silver has turned black, you may need to polish it using an agent. Precipitated chalk works wonders. The chalk needs to be mixed with water to create a thick paste. Start with three teaspoons of chalk and add a quarter to half a teaspoon of water, stir the water in and continue to add small amounts of water as much as needed until you have a paste.

Rub the paste on the silver using a cotton pad (or a super soft toothbrush, like for babies, for intricate silverwork such as granulation) and gently polish the surface. After polishing, rinse the object thoroughly and make sure no dried chalk is left.

This method is unsuitable for hollow objects, as the rinsing may cause water and chalk residu to end up inside your ornament. Bring these to a professional.

Pro: works really wel

Con: chalk needs to be extremely finely ground to avoid scratching, your brush may also cause scratching, intricate designs need to be rinsed thoroughly, can not be used on hollow objects. Removes a bit of the surface: it will tarnish faster if not stored well.

Method 3: baking soda

The black tarnish can also be removed by submerging it in a baking soda bath. This reverses the process that caused the tarnishing.

Line a bowl with aluminum foil, add a couple of tablespoons of baking soda, sprinkle in some salt and add boiling water. When the water calms down after bubbling, submerge your silver items and let soak.

Again: do not use this method on items that contain anything else than silver, like beads, coral, enamel etcetera, or on hollow pieces.

Once you put your item in, you will see it cleaning up within seconds. Take the silver out as soon as the tarnish disappears (use gloves!), rinse under lukewarm water, dry thoroughly with a soft cloth and polish with a polishing cloth.

Pro: cleans very fast

Con: unsuitable for hollow objects, pieces you don’t know the silver content of, and pieces with anything else than silver. Removes a bit of the surface: it will tarnish faster if not stored well.

Cleaning ethnic jewellery: keep track of what you did

And finally, make a note of your cleaning treatment in your object files. What you will want to note here are the date and the type of treatment, and if needed a before-and-after picture. This will help you keep up with your routine checks on your collection: silver should be polished as little as possible, and a cleaning log helps to keep track!

Cleaning ethnic silver jewellery: the round-up

So, as you see, the decision to clean ethnic jewellery is one that requires some thought. Don’t start overcleaning it, but don’t let it get too dirty, either. One thing is certain: leaving it grimy is not authentic, and even outright damaging to your jewellery. And when in doubt, bring your jewellery to a professional restorer – this way, you’ll have the best of both worlds!

—

More tips for collectors? Browse them all here!

Join the Jewellery List and find regular jewellery news in your inbox!

—

References

Read more here on treatment of silver and copper alloy objects (opens a pdf)

Would you like to quote this article? Please do! Here’s how:

S. van Roode, [write the title as you see it above this post], published on the Bedouin Silver website [paste the exact link to this article], accessed on [the date you are reading this article and decided it was useful for you].

Sigrid van Roode

Sigrid van Roode is an archeologist, ethnographer and jewellery historian. Her main field of expertise is jewellery from North Africa and Southwest Asia, as well as archaeological and archaeological revival jewellery. She has authored several books on jewellery. Sigrid has lectured for the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Turquoise Mountain Jordan, and many others. She provides consultancy and research on jewellery collections for both museums and private collections, teaches courses and curates exhibitions. She is not involved in the business of buying and selling jewellery, and focuses on research, knowledge production, and education only.